Waterstradt Home Page

Shania page - a Waterstraat cousin

Waterstraat History Books

Storys

Waterstradt Women

Zany Items

Waterstradt Immigration and Homesteading

More Waterstraat History

Waterstradt Land of Old Germany

Employment and schooling

Contact Page

Waterstraat Holidays

Favorite Links

Personal Page and Miscellaneous Items

Newspaper Items

Historian's Page

Guest Book Page

|

WATERSTRAAT IMMIGRATING AND HOMESTEADING

Waterstraats immigrated from Germany primarily to the Dakotas, Nebraska, New York, Wisconsin, and Illinois.

ONE OUT OF THREE MECKLENBURGERS LEFT HIS COUNTRY

In the middle of the past century Mecklenburg was one of the areas in Europe that was most affected by the emigration movement. Mass emigration is a sign of severe social crisis in any country. What reasons did so many people have to leave their country and hope for a better life abroad in the 19th century?

The emigration wave was not limited to Mecklenburg alone. It also covered all other parts of the fragmented German Empire. In all, several million people emigrated from Germany. The emigration movement spread to other European countries as well, but Mecklenburg was especially hard hit. In fact, after 1850, Mecklenburg had the third highest emigration count in Europe, superceded only by Ireland and Galicia ( land which is currently Poland

and the Ukraine).

"And why have you left Germany?" asked Heinrich Heine in 1834, when he met some German emigrants in France on their way to North Africa. "The land is good, and we would have liked to stay", they replied, "but we just couldn't stand it any longer."

If asked that same question, many of the 261,000 Mecklenburgers that left their home country (the Grand duchies of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz) between 1820 and 1890 would have given the same answer. Many people, especially those from the lower social classes, didn't have any prospects or future in Mecklenburg, since their lives were totally uprooted by the change from feudal rule to a civil-capitalist one.

Between 1850 and 1890 approximately 146,000 Mecklenburgers emigrated overseas, most going to the United States of America, but some also going to South America. Between 1820 and 1890 those going overseas accounted for two thirds of all the emigrants from Mecklenburg. The defeat of the civil-democratic revolution in 1848/49 and

the return of the old social and political problems gave fresh impetus to this emigration movement.

This loss of population was most prevalent from the so-called flat or farm land. 88.5 % of all emigrants came from rural areas. Most of them came from the lands of the knights, from the manor houses of noble and titled big land-owners. These were the people who had the most compelling reasons for leaving Mecklenburg. This was mostly due to the miserable social conditions caused by the right of abode and the right of establishment rules which existed almost unchanged between 1820 and 1860.

These conditions came about when serfdom was annulled in Mecklenburg in 1820/21. At that time, many landowners took the opportunity to get rid of a lot of their day laborers who were now considered personally free according to the law. They began to run their lands with a minimum of permanent workers. The landowners did this so that they would not have to pay for any laborers who were injured or take care of them when they grew old. It was very difficult for day-laborers who were thrown out to find permanent work elsewhere because they needed to

receive the right of establishment from the new employer. But that wasn't easy to get.

In 1861, an expert on Mecklenburg history, Ernst Boll, explained the right of abode and right of establishment in his Abriss der Mecklenburgischen Landeskunde this way: "a Mecklenburger does not belong to the country as a whole as far as his home is concerned. Rather, he belongs to the one city or village that he happens to be born in, or to the city or village where he has received the right of establishment."

The granting of the right to marry also depended on the granting of the right of establishment. and all subjects needed permission to marry before they could have a family. A man or woman who did not have the right of establishment could never establish a home. Therefore, the main problem for a common Mecklenburger was to get his own "Hüsung", but many did not succeed. A lot of people that worked as needed paid laborers were refused the right of establishment by the ruling class for their whole lives. They were given only a limited right to residence - only for as long as they had work. These were the inhumane conditions that existed. Mecklenburgers could become homeless in their own country.

Therefore it is no surprise that tens of thousands decided to emigrate rather than walking around homeless. In fact, the knights and landowners encouraged emigration at times. The loss of population in rural areas grew larger and

larger. While there still was a population growth of 55,000 people between 1830 and 1850 despite the emigration, new births could not make up for the high number of emigrants between 1850 and 1905. The rural population dropped by 25,000.

After the German Empire was founded in 1871, industrialization spread and some cities expanded rapidly. The number of people that emigrated overseas decreased, and internal migration increased. More people that were willing to emigrate went to cities and industrial towns outside of Mecklenburg, such as the areas of Berlin and

Hamburg rather than to America.

In 1900 approximately 224,692 people who were Mecklenburgers by birth lived outside of their home country. That was almost one third of the Mecklenburg total population. On December 1, 1900 there were 53,902 emigrants from Mecklenburg-Schwerin living in Hamburg-Altona.

Article from the "Mecklenburg Magazin" 1990/9 by Dr. sc. Klaus Baudis, translation: Daniela Garling

Atlantic crossing

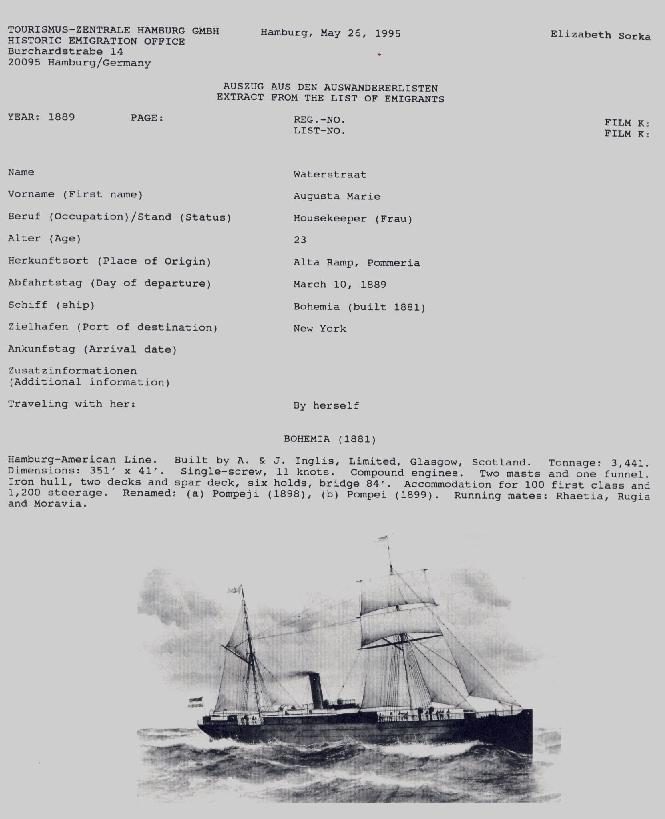

A WATERSTRAAT LADY TRAVELLING ALONE TO AMERICA.

(written by Augusta Marie Waterstraat)

Though I had means enough to live economically in Altefar for two years working as a maid, I resolved to put my good resolutions into practice at once, and save money by taking passage in the steerage, in spite of the protestations of my family. I selected one of the steamers, not that the price is lower, but because travellers of experience had told me that the space (for one cannot designate it otherwise) alloted to the steeragers was larger, and the treatment, on account of the small number of passengers, more humane.

Only some intimate friends accompanied me to the steamer, while several important members of my family made themselves conspicuous by their absence, feeling ashamed no doubt of such poor surroundings; and true enough the "taking leave" was as

simple as possible, without champagne and large wreaths of flowers.

When Alta Ramp was out of sight the steeragers were driven down stairs in a file to perform their first office and show their tickets to an officer, who tried to suppress all his colleagues in a harsh voice and rough manner. The last I saw distinctly of

Germany was the docks.

Down-stairs I looked for the head steward and bribed him with a fee to give me as good a berth as possible. I was put into an apartment, a narrow aisle with two rows of beds on either side, originally meant for twenty-four, but now occupied only by twelve persons, which allowed each an empty berth to stow away one's baggage. I was at a difficulty to guess what I would have done otherwise. An upper bed fell to my lot, in one of the corners near the window, and so I was protected at least on one side. My neighbor was a half-crazy German woman, with exceedingly dirty habits and unkempt appearance; she had a weakness for using her lap as a dish for sauerkraut, potatoes and herring during meals, but otherwise overwhelmingly

benevolent, offering me a whole assortment of eatables she had brought with her. The rest of the beds were occupied by women and two married couples, and the presence of the men, though they behaved quite respectably, I did not find very appropriate. But these are the small annoyances attending a cheap trip!

Thus the pleasure of giving one's self a good washing or of changing one's underwear was denied us during the whole voyage.

Nor had I forgotten to provide myself with a number of canned eatables, fruit and candy, but all these things which I considered delicacies on land I expressed a dislike for after two days out at sea.

"Well, you will have to try and get along with the steerage food," remarked the good humored steward, ladling the pea soup out of a huge pail with much unnecessary splashing, but I could not manage it. The food in itself is plentiful and good enough -

though singularly tasteless, being cooked by steam - at least for the majority of the steerage passengers, who have hardly anything better on land. The universal outcry against the food was perhaps to be explained by the fact that most people lose

their appetites at sea and would experience an aversion for the best food.

The first night when I climbed up to my bed with its mattress and blanket for which I had paid twice its value, I felt very homesick and wept silently in my squalid surroundings.

I was awakened in the night by the loud cries of a Polish woman beneath me. This woman was my special aversion, she surpassed my German neighbor in her unkempt, dirty appearance, and was suspected of harboring vermin, The cause of her cries was a bottle of wine in my berth, which had been carelessly corked and now was spattering down into the bed below. My efforts to explain matters and proffer excuses were in vain, for the reason that the Polish woman did not understand a word of German. Some of the occupants thought her worthy of assistance, while others took my part. Our peaceful neighbors became two hostile camps, there was an exchange of invectives, cutting sarcasms, a din of crying children, and order was only restored with

the intervention of the steward, who was on watch all night.

In the meantime the ship was beginning seriously to rock, and groans and sighs told us that our neighbors were feeling seasick. The air was as close and foul as I could imagine it, as the sea, splashing in at the windows soaking our beds and robbing us of the last shreds of comfort, caused the ventilators to be closed. At the break of day, I started from my broken sleep, jumped out

of bed, ready dressed as I was, and groped my way on deck. I felt the time had come to pay my tribute to Neptune. The decks were streaming with water, getting their early washing, the huge stormy sea stretching to the horizon, and the dull sky

above seemed all steeped in a sickly gray, and a number of seagulls fluttered over the red water.

An officer went by smiling, no doubt at my appearance, with dishevelled hair, shivering in an old wrapper, covered with white flocks from the bed blanket I had slept in.

Days of misery began for us poor steeragers. The sea beat on the deck, drenching us to the skin, the rain fell in torrents and the ship's tossing made life unbearable. Seasickness under such conditions is a capital means of torture. One stands for days in wet

shoes and stockings, which cannot dry over night and have to be donned wet in the morning, our clothes are damp and ill-smelling, from being worn wet and in bed; chilled to the bone and racked with fever, one finds no rest on the hard straw and the short beds. And what with the noise of so many congregated in so small a space and the odor of people who have not changed their garments for months, without a breath of air in the tightly closed space, one may no doubt begin to regret an economical tendency. It is especially sad to notice the little children; during the stormy weather they crept away from sight, pale and sick, and no joyful word or play enlightened these little mortals; they could not eat the food, and dirty and sad lay about where they could.

Yet all things come to an end, and the bad sea and gray sky were succeeded by calm and sunshine. The girls came out in holiday attire, the children began to play and the windows were opened.

Our appetites also increased, and it became a serious question as to how we could bribe, coax and induce the officials to give us better rations. The steeragers provided with money had food smuggled to them, which was termed "cabin food," but was

merely that of the lower officials. Twice a day I stole with a tin dish into a certain pantry situated under the cabin and was served with a large portion of "cabin" food by a little fat jolly cook's help, who grew grave when he cast a look up at the

captain, absorbed in the contemplation of the horizon. Selling of eatables was prohibited, but as the pastry cook also wished to make money, I was in addition well provided with cakes and biscuits.

As there were no conveniences for dining, each passenger had to climb into his bed with his food and there partake of it. Moreover, one has only one plate for soup, meat and dessert, and the knife is so blunt or the meat so tough that the rest of the

food spatters over the bedclothes before the tussle is over.

As for the climbing into bed I had acquired a tolerable proficiency in it, and made it a matter of a second. I stepped on the lower bed, turned swiftly, and with a skillful movement lifted myself and landed in the tiny birth. Another disagreeable thing, because combined with great difficulties, was the washing of the dishes; there being a great deficit of fresh water, one wavered between the alternatives of rinsing the things in cold salt water, or of leaving them as they were. In any case the knives were never free from a thick coating of rust.

A thing which will always prove interesting in steerage is the study of the different passengers, numbering about 1200 during the trip in question. Almost every European nationality is represented. There were Poles in gray linen suits of peculiar ..., with baggy pants and high-heeled topboots; Hungarians with dusky skins, large slouched hats and brown capeulters, looking for all the world like stage brigands; Norwegians in red shirts and fur caps,; Frenchmen in brown velvet suits from the vineyards of France.

Polish Jews, who were dressed entirely in rags, of every shape and description, the majority old women with beaked noses and witch-like faces, young women fading early, and beautiful large-eyed children. These Italians were very amusing to watch; they

lay around on deck, stretched at full length, huddled against each other under a ragged blanket. They were continually jabbering and quarrelling, and eating onions. The men of the family were entirely swayed by the old women, and there was generally a

wrangling over money. One of them confided to me that after landing in New York on his first crossing he promenaded up Broadway, but he had scarcely gone a mile when the traffic and bustle so frightened him that he at once made his way back to the pier and bought a return ticket for the old country. The Italians were conspicuous by [being] continually absorbed in the game of maro, a rather stupid game, but capable of making them exceedingly excited and noisy. They seemed quite well provided with money and were merely making a pleasure trip.

The good weather also brought another pleasure. The captain ordered the hand-organ to be played, which a little sailor ground away at for hours. Dancing was not very energetic, however. Less delightful was the sailor's band consisting of a fiddle, a harmonica, a trombone, a drum and two tin lids as cymbals, which last two generally deafened the rest of the instruments. Strange to say, nobody could make out what tune they were performing; for instance, they once announced that they had just played the "Wachtam Rhein" to everybody's amazement; they tried again, but the audience had to join in singing the tune themselves in order to get some idea of it.

By this time my mattress had worn so thin that I felt the iron bars through it and lay awake for whole nights. The steward shrugged his shoulders when I complained but brought me a new mattress soon after and enlivened my afflicted body with hot rolls, with the compliments of the pastry cook.

All our hopes and interests were now centred in the end of our voyage. With what pleasure did I greet the first vessel after a monotonous week of sea and sky! It was a beautiful sight, a full-rigged vessel with its white sails expanded and swayed by strong breezes, rising up and down on the undulating waves, reminding me of a fairy ship or one of the old Spieluhren [?] we have at home.

What sensation the first lighthouse created among the passengers, the "cabin gentlemen and ladies," affecting a peculiar walk to express their superiority and unapproachableness, trod the steerage ground to inspect the land on either side. The last day brought beautiful weather and a calm sea; numerous ships, sailing vessels, and fishing smacks covered the waters; steamers bound to and from America, with their enormous loads of steerage passengers, passed us now and then amid mutual cheerings. There was plenty of music, and the liquor flowed extravagantly; the sailors and our good stewards thought it time to begin their sprees,

and were very gay and uncertain about the legs. Nobody wished to go to bed, and when driven down at last, they busied themselves packing and dressing in spite of being warned by the officer that they would not land before nine next morning, and for those few who lay quietly in bed sleep was made quite impossible.

When the people found out at last that it would take several hours to affect the landing they wished to refresh themselves a little with some sleep, but to punish their folly they were all sent on deck, which was being washed with a great fury. The people

crowded together like a flock of sheep in a thunderstorm, trying in vain to find a dry spot. At last we touched the landing place and the bridges

were let down. The steeragers were very anxious to reach land and pushed themselves among the cabin

passengers, some of whom seemed to begrudge their escaping from their misery as soon as they could.

The voyage took a total of 16 days. I arrived in New York on March 26, 1889. In New York harbor I transferred to a ferry which took me through customs at Castle Garden. I then took a train to Elma, here in Nebraska.

Agusta Marie Waterstraat

An article from the Grand Island newspaper, November 16, 1890

-------------------------------------------------

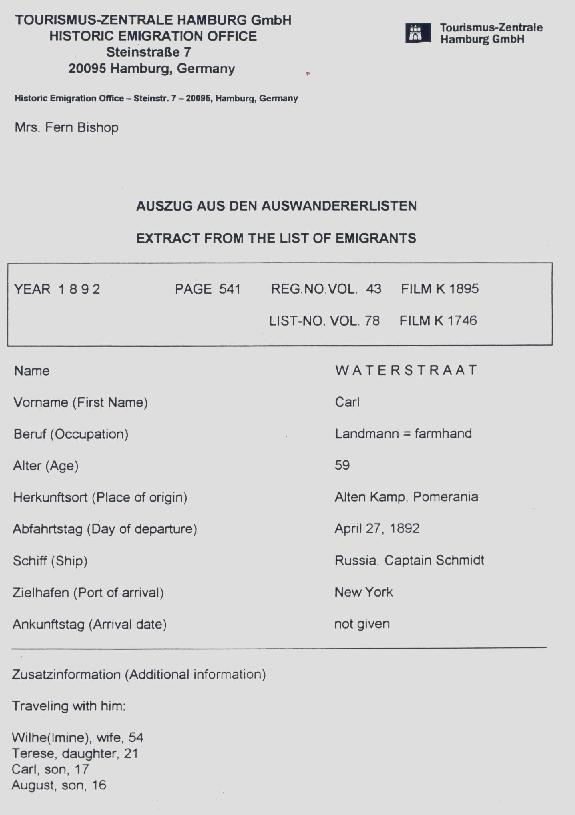

2 MORE WATERSTRAATS CROSS THE ATLANTIC

ON THE SS BOHEMIA

SS Bohemia Page 4 of 10 (partial - Page 9 still being transcribed)

Hamburg, Germany & Havre, France to New York

November 16, 1881

DISTRICT OF NEW YORK - PORT OF NEW YORK

I, C. Pezalot, Master of the SS Bohemia do solemnly, sincerely, and truly swear that the following List or Manifest, subscribed by me, and now delivered by me to the Collector of the Customs of the Collection District of New York, is a full and perfect list of all the passengers taken on board of the said Bohemia at Hamburg & Havre from which port said Bohemia has now arrived and that on said list is truly designated the age, the sex and the occupation of each of said passengers, the part of the vessel occupied by each during the passage, the country

to which each belongs and also the country of which it is intended by each to become an inhabitant: and that said List or Manifest truly sets forth the number of said passengers who have died on said voyage and the names and ages of those who died. So help me God. (signed) C. Pezalot? Sworn before me this Nov. 16 1881, signed: R?ynm????

List or Manifest of all the Passengers taken on board the SS Bohemia whereof C. Pezalot, is Master, from Hamburg & Havre burthen (left blank) tons.

Columns represent: given name, surname, age, sex, occupation, country to which they belong, country which they intend to inhabit

560 Christine Waterstraat 67 f wife Mecklenburg U S

561 Marie Waterstraat 28 f daughter Mecklenburg U S

562 Friederieke Kansow 19 f wife Mecklenburg U S

563 Albert Kansow 11ms f*babies Mecklenburg U S

564 Meta Kansow 1ms f*babies Mecklenburg U S

565 Carl Kuhl* 20 f*farmer Mecklenburg U S

566 Friedr.* Strupp 59 f*workman Mecklenburg U S

567 Marie Dohse 18 f single Mecklenburg U S

568 August Mundt 25 f*single Mecklenburg U S

569 Elise Boldt 40 f wife U S U S

570 Albert Boldt 8 m children U S U S

571 Charles Boldt 6 m children U S U S

572 Heinrich Boldt 11ms m baby U S U S

573 Johanne Dammann 64 m workman Mecklenbg U S

574 Friedericke Dammann 60 f wife Mecklenbg U S

575 Therese Dammann 26 f daughter Mecklenbg U S

576 Carl Balz 27 m workman Mecklenbg U S

577 Friedr.* Dohse 16 m farmer Mecklenbg U S

578 Joh.* Blantz 27 m cartwright Prussia U S

579 Heinrich Fromm 32 m workman Mecklenbg U S

580 Dorothea Rieckhoff 20 f single Mecklenbg U S

581 Joh.* Paters 34 m farmer Mecklenbg U S

582 Friedericke Paters 30 f wife Mecklenbg U S

583 Wilhelmine Paters 5 f children Mecklenbg U S

584 Anna Paters 4 f children Mecklenbg U S

585 Joh.* Paters 9ms m baby Mecklenbg U S

586 Mathilde Friedman 20 f single Austria U S

587 Elisabeth Teufel 24 f single Wurtemberg U S

588 Marie Bienzle 18 f single Wurtemberg U S

589 Karl Kumisch 13 m boy Wurtemberg U S

590 Ottilier Haulinsaek 16 f single Wurtemberg U S

591 Rupert Graf 20 m farmer Wurtemberg U S

592 Julius Hoffmann 19 m printer Bavaria U S

593 Marie Schmitt 16 f single Hessian U S

594 Ph.* Bassauer 57 m Brewer Hessian U S

595 Peter Lawall 21 m single Hessian U S

596 Marie Peters 26 f single Hessian U S

597 Auguste Voss 24 f single Hessian U S

598 Johannes Hauck 24 m farmer Hessian U S

599 Johannes Fulich 15 m farmer Mecklenbg U S

600 Friedr.* Haliekost 28 m farmer Mecklenbg U S

601 Caroline Scharfenstein 24 f single Hamburg U S

602 Elise Johnsen 19 f single Hamburg U S

603 Chr.* Volk 30 m Tailor Hessian U S

604 Fritz Englert 24 m Cooper Bavaria U S

605 Eva Ahlheim 20 f single Bavaria U S

606 Barb.* Wieder 50 f wife Bavaria U S

607 Joh.* Weider 8 m son Bavaria U S

608 Nic.* Saueracker 30 m cooper Bavaria U S

609 Carl Kramer 19 m workman Hessian U S

610 Chr.* Popp 29 m sheapherd* Hessian U S

611 Jacob Sabbath 26 m farmer Bavaria U S

612 Georg Guthy 40 m Brewer Hessian U S

613 Elisabeth Guthy 37 f wife Hessian U S

614 Catharina Guthy 8 f children Hessian U S

615 Marie Guthy 7 f children Hessian U S

616 Lucie Guthy 6 f children Hessian U S

617 Elise Maurer 16 f single Hessian U S

618 Heinr.* Mann 17 m saddler Hessian U S

619 Margaretha Mayer 74 f wife Hessian U S

620 Jacob Mayer 8 m child Hessian U S

621 Heinrich Hahl 30 m Taylor* Hessian U S

622 Elisabeth Hahl 35 f wife Hessian U S

623 Marie Hahl 5 f children Hessian U S

624 Heinrich Hahl 3 m children Hessian U S

625 Jacob Hahl 9ms m baby Hessian U S

626 Franz Bidrmann 29 m workman Austria U S

627 Franziska Bidrmann 31 f wife Austria U S

628 Franz Bidrmann 3 m son Austria U S

629 Joseph Bidrmann 11ms m babies Austria U S

630 Karl Bidrmann 1ms m babies Austria U S

631 Christian Treu 27 m farmer Mecklenburg U S

632 Lisette Treu 27 f wife Mecklenburg U S

633 Anna Treu 7 f children Mecklenburg U S

634 Ludwig Treu 4 m children Mecklenburg U S

635 Christiane Treu 22 f wife Mecklenburg U S

636 Wilhelmine Treu 11ms f baby Mecklenburg U S

637 Fritz Mentz 28 m Taylor* Mecklenburg U S

638 Andreas Twardy 43 m workman Prussia U S

639 Rosalie Twardy 33 f wife Prussia U S

640 Hendrick Twardy 8 m children Prussia U S

641 Vincenz Twardy 6 m children Prussia U S

642 Marie Twardy 4 f children Prussia U S

643 Johannes Twardy 11ms m baby Prussia U S

644 Stefan Wadehofsky 23 m workman Prussia U S

645 Apollonia Wadehofsky 24 f wife Prussia U S

646 Stanislawa Wadehofsky 11ms f babies Prussia U S

647 Stefan Wadehofsky 1ms m babies Prussia U S

648 Johanie Netzer 16 f single Austria U S

649 Mariane Nowak 18 f single Austria U S

650 Franziska Nowak 16 f single Austria U S

651 Mariannie Klukow 18 f single Prussia U S

Transcriber's Notes:

* No deaths on pages 10, 11 or 12 during the voyage.

* ? indicates a word or letters that could not be read due to quality

of original document, recorder's penmanship (which was very nice)

and/or transcriber's skill.

* * indicates an explanation in the "Notes"; i.e., abbreviation,

gender correction and/or occupation, etc.

* Original manifest numbered the passengers thusly: 490, 1, 2, 3, 4,

5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 500, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6,-----510, 1, 2, ; etc.

* I completed the numbers for ease of identifying notes.

* The recorder extensively used ditto marks in the columns for

Sex, Occupation & country of origin. I inserted the words that the

ditto marks represented. In the cases of one or more children in a

family the recorder bracketed the lines and wrote "children" or

"babies" in a slant. In those cases I repeated the word he used.

* In the Final Destination column the recorder placed the letters

U S (we assume he meant United States[of America]) and then a wavy

line from top to bottom. In this case I repeated the letters throughout.

* Surname in passengers 512 to 515 could be HENER or HEUER.

* The recorder abbreviated First names in several places:

Wilh. meaning Wilhelm/male or Wilhelmine/female;

Joh. for Johanes or Johannes;

Friedr. for Friedrich/male, or Friedericke/female;

Ph. could mean Philip?;

Chr. possibly Christian or Charles;

Christ. for Christian;

Herm. possibly Herman;

Nic. for Nicolai or Nicolas?

Heinr. for Heinrich?

Barb. for Barbara?

* Under "Occupation," the recorder misspelled "shepherd" (on 610)

and tailor (on 621 and 637).

* With the recorder's use of ditto marks in the "Sex" column he forgot

to change the letter a few times:

563 is m/male;

564 could be m/male;

565 is m/male;

566 is m/male; not sure on

568 August, could possibly be m/male in the Deutsch language an "e"

should end the name in the feminine. I judged from the first name of

the person.

* The umlaut is over the "u" in Kuhl.

-------------------------------------------------

BOHEMIA

The "Bohemia" was built by A&J.Inglis & Co, Glasgow as the "Bengore Head" for the Ulster Steamship Co. She was a 3,410 gross ton ship, length 350.5ft x beam 40.2ft, one funnel, two masts, iron construction, single screw and a speed of 12 knots. Accommodation for 100-1st and 1,200-2nd class passengers. Launched on 25/8/1881, she was

sold to Hamburg America Line on 30/9/1881 and left Hamburg on her maiden voyage to New York on 30/10/1881. On 16/3/1892 she commenced a single round voyage from Hamburg to New York and Baltimore, and on 17/5/1893 commenced her first voyage between Stettin, Helsingborg, Gothenburg, Christiansand and New York. She started her last voyage between Hamburg and New York on 2/4/1897 and on 11/6/1897 commenced sailings between Hamburg, Philadelphia and Baltimore. In 1898 she was sold to the Sloman Line of Hamburg, renamed "Pompeji" and made three Hamburg - New York voyages before being sold to an Italian company in 1900 and being renamed "Pompei". She was scrapped in 1905 at Spezia, Italy.

|

|

More Waterstraats Immigrating

SS RUSSIA - the ship these Waterstraats took:

Hamburg-American Packet Company/Packet Company

Formed in 1847, the Packet Company sailed from Hamburg to New York via Southampton. In the early years sailing time was about 40 days, Hamburg to New York. In 1875 the company took over the Adler Line, and in 1886, amalgamated with the Carr-Union Line. They assumed control of the passenger management of Hamburg-South America Line, German East Africa Line and Hansa Line's Canadian service in 1888. The five vessels of the Eagle Line were purchased when that

company collapsed and, about 1890, they took over the Hansa Line. In 1930 Hapag Lloyd Union was formed with North German Lloyd, and in 1970, the company combined with North German Lloyd to become Hapag-Lloyd AG.

By 1872 the company was making weekly passages to New York and had extended their service to include Baltimore, the West Indies, Mexico, South American, China, Japan and Australia. Service was extended about 1873 to include routes from Hamburg, Antwerp and Montreal in the summer and Hamburg, Antwerp and Boston in the winter.

To avoid competition in the Mediterranean the Hamburg-American and the North German Lloyd Line agreed to run a joint service in that area. They sailed from Algiers, Naples and Genoa to New York.

Vessel: Russia

Tons: 3,908

Years in Service: 1889 - 1895 then 1896 - 1899

sold to Cia Trasatlantica in 1895, renamed Santa Barbara, 1896 repurchased reverted to Russia, 1899 sold to Russian Steam Nav.Co, renamed Odessa.

|

|

Filing for a new homestead in Nebraska

One of many homestead filings in our data base

|

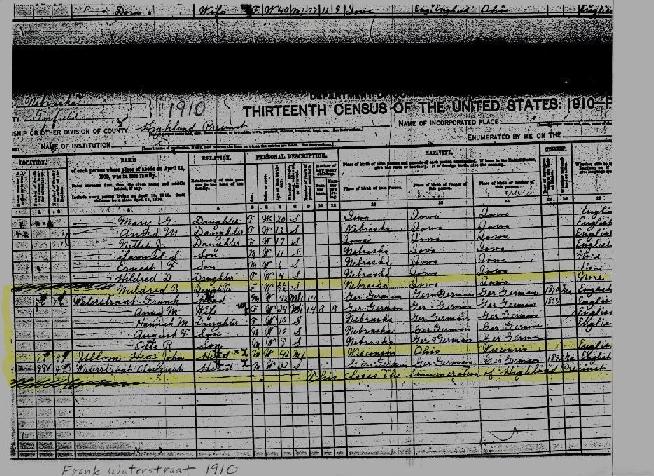

Nebraska Census

One of the Garfield County homestead census records

|

Special Thanks:

To Kevin Brown, Fern Bishop, and the U.S. government for most of these photos and documents!

|

|